Why Being A Little Cold Can Actually Help You In Winter

Especially if your people came from colder places

Every winter, my first instinct is the same as everyone else’s:

Pile on the socks. Turn up the heat. Complain🤣.

Cold feels like something we are supposed to escape. Get from the house to the car to the store as fast as possible. Warm shower, warm bed, warm everything. I mean, the smell of the heater turning on in the winter might be one of my favorite things ever.

But if you zoom out for a second, our biology tells a different story.

We carry mitochondria that came from our mothers, who got theirs from their mothers, and so on, all the way back. For a lot of us, that maternal line lived in places that were cold, dark, and seasonal. So, winter was not a glitch in the system. It WAS the system.

And our mitochondria had a way of dealing with that.

This is where “gentle” cold comes in, and it is very different from cold plunging (more on that later).

I am talking about slightly cooler water, a little longer, with a totally different goal.

Heads up that I’m getting into a lot of topics here because they all feel very connected, important, and relevant. Here’s what I’m covering in this post:

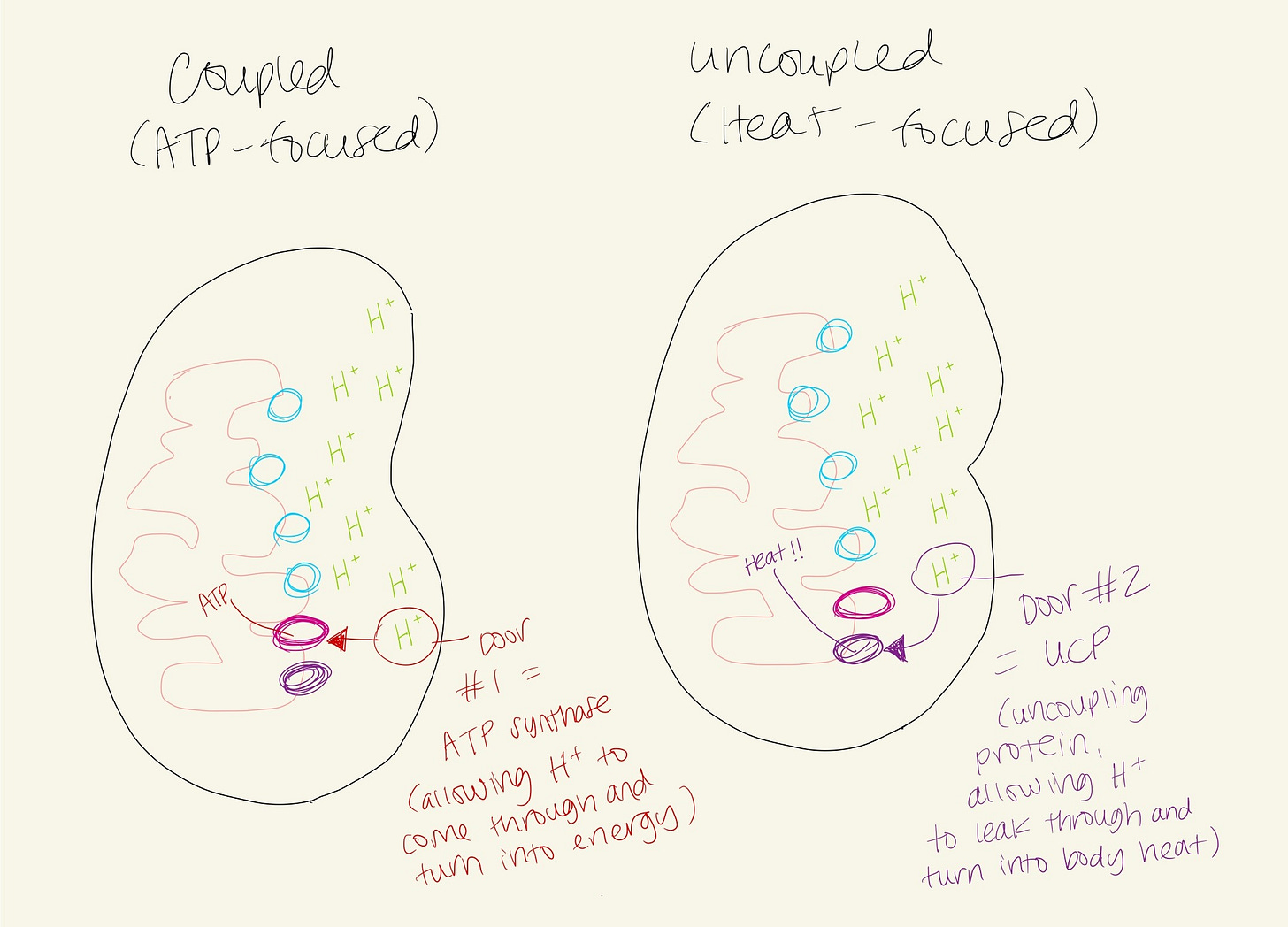

🔬 Coupled vs. uncoupled: what your mitochondria actually do with fuel

🏔️ Why this hits different if your maternal line came from colder regions

🥶 How “gentle” cold compares to the cold plunge trend

💧 Cold water vs. cold air

💡 Internal light, and how your body acts as…essentially a semiconductor

💛 What incorporating this could look like in real life

🫶 How this fits the bigger story

It’s a topic I care a lot about, which means I tend to go deep.

So…here we go

Coupled vs uncoupled: what your mitochondria actually do with fuel

Quick refresher on mitochondria without turning this into a textbook. Maybe you’ll remember some of this from science class.

Most of the time, mitochondria are in “coupled” mode.

You eat food.

You break it down and send electrons into the mitochondrial electron transport chain.

Protons build up on one side of a membrane and then flow back through ATP synthase (one of the last parts of the electron transport chain that is responsible for making ATP).

You make that ATP (your energy currency).

In a coupled state, most of the proton gradient is used to make ATP. There is always a little leakage and heat, but the main goal is efficient energy production.

Cold changes that.

Your body has another option called uncoupling.

When you’re cold, your body can literally choose to make heat instead of ATP in certain tissues, especially brown fat. In these cells, a protein called UCP1 acts like a second door in the mitochondria. Normally, protons flow back in through door #1 (ATP synthase) to make ATP. But cold exposure switches on UCP1, opening door #2.

Protons flow back through the membrane without going through ATP synthase.

Instead of making ATP, more of that gradient is released as heat.

You burn more fuel to stay warm, and you generate a lot of internal warmth from the inside out.

That is uncoupling. Less efficient if you only care about ATP. Very helpful if you care about surviving winter with decent circulation and a working brain (hi! 🙋♀️).

With repeated, milder cold (think “I’m chilly” rather than “I’m going to die”):

Brown and beige fat get better at turning on this heat response

Mitochondria in those tissues become more numerous and more resilient (mitochondrial biogenesis)

Old, damaged mitochondria are more likely to be cleared out (mitophagy)

Human studies using mild cold acclimation… for example, spending several hours a day at 57–59°F (14–15°C) air for about ten days… have shown big improvements in insulin sensitivity (around 40% in people with type 2 diabetes) and changes in how muscles and fat handle glucose (Hanssen et al., 2015). Other work links cold-activated brown fat to better glucose and lipid metabolism overall (Peres Valgas da Silva et al., 2019).

In other words, mild, sensible cold can be a seasonal reset button for your mitochondrial network and your metabolic flexibility.

Why this hits different if your maternal line came from colder regions

As mentioned, mitochondria are inherited from your mother, her mitochondria came from her mother… and so on.

Over many generations, people whose maternal lines lived in colder, darker climates often ended up with mitochondrial adaptations that helped them:

uncouple more easily

tolerate cold better

use fat as fuel for heat production

make the most of winter

There are even population-level hints of genes that tweak brown fat and cold tolerance in groups like the Inuit, likely as an adaptation to chronic cold (Fumagalli et al., 2015).

This does not mean that cold is “bad” for anyone else. It just means:

For some of us, a little cold is not an attack on our system. It is exactly what our mitochondria expect at certain times of the year.

And in a world where we keep the thermostat at 72, live under artificial light, and never really send “winter” signals to the body, those built-in adaptations do not get used.

They just sit there.

And this mitochondrial haplotype is totally me. My maternal ancestors are from Poland, Germany, and more (TBD). And though I don’t like getting cold initially (ok, kind of hate it), after I do, it feels insanely revitalizing.

And to be clear, this is not about the cold plunge trend

Cold exposure has become trendy in the last few years, mostly as very intense, very short, very “watch me suffer” plunges.

That version is focused on:

big adrenaline and norepinephrine spikes

mental toughness and resilience

short-term mood and focus benefits

That is a different tool. It can be useful for some people; it has some incredible benefits. It can be dangerous for others in certain scenarios. And for women, it really depends on cycle timing and water temperature.

I actually own a cold plunge 🤣 and love, love it. I typically use mine around 50-55 degrees.

To sum this internal process up, really, you can imagine two different programs.

Very cold, very short → nervous system shock, catecholamine surge, “I feel alive,” mental resilience.

Cooler, longer → brown/beige fat training, mitochondrial remodeling, better fuel handling, quieter but deeper metabolic effects.

When practitioners talk about time × temperature, this is what they mean: you don’t have to chase 39°F to get benefits. You can choose slightly warmer water, stay a bit longer (safely), and aim for a gentler, more metabolic signal instead of a full-on stress test.

The kind of cold I am interested in for winter is:

less extreme

more gentle

more about mitochondrial health and seasonal signaling than about “how much can you tolerate”

Think:

slightly cooler water

slightly longer sessions

less “shock,” more “reset”

You should not feel panicked or out of control. You should not be gasping for air. This is not a punishment. It should feel natural (and, considering this means not being wrapped in a cozy blanket 🙃… a little uncomfortable).

Quick note before we get too nerdy: nothing I share here is ever medical advice. I just genuinely enjoy digging into the science and translating it into real life, but it is not a substitute for your own health care team. Please check in with your provider before changing your routine or trying anything new, especially if you have existing health conditions or take medications.

Why water, not just air

You have probably noticed this already, but:

50 degrees in air feels one way

50 degrees in water feels like a whole different universe

Water pulls heat from your body much faster than air does. That is why even mildly cool water can have a strong effect on your core temperature.

From a mitochondrial perspective, that is useful.

You can:

use water that is only a bit cooler than you are

let your core cool a little

send your body a clear “it is cold now” signal

Without needing to do snow angels in the snow.

(Which reminds me how much fun it was in my ol’ Colorado days going from the hot tub —> laying in the snow —> hot tub. This was hot-cold therapy at its finest without me even realizing what was happening physiologically.)

Think of it like this:

A hot bath is water that is hotter than you that warms you up.

A “mitochondria bath” for winter can be water that is cooler than you that gently invites your body to turn on its own internal heat.

You do not have to jump straight into ice.

You can start with:

slightly cooler baths

finishing your shower cooler than you normally would

brief soaks in cooler water where you still feel safe and in control

But wait…there’s another really important part to all of this.

I want to talk briefly about internal light, and how your body acts as…essentially a semiconductor

Because I find it insanely fascinating, and though it’s not talked about much, there is a lot of research and science to back it up fiercely.

This is where it can start to sound woo, so let me stay grounded.

Mitochondria are not only making ATP and heat. When they run, they also emit a tiny amount of light, often in the red and infrared range. These are called ultra-weak photon emissions or “biophotons.” You cannot see them with your eyes, but sensitive instruments can (Tafur et al., 2010; Van Wijk et al., 2020).

You can think of this as:

a tiny, constant glow of activity

a reflection of how energy and electrons are flowing through your tissues

Zoom out from mitochondria and look at the whole body, and this is basically the world Robert Becker discusses in his book, The Body Electric (an incredible read that I highly recommend):

Collagen-rich tissues and fascia are full of ordered water.

That water + collagen combo can behave like a liquid crystal, helping charges and protons move along fibers (Matsui & Matsuo, 2020).

Some researchers even describe this as a biological semiconductor (not a hard silicon chip, but a soft, living network that carries direct currents and repair signals).

Cold-driven uncoupling and mitochondrial renewal can:

→ help clear out damaged mitochondria

→ encourage the growth of new ones

→ increase heat and infrared production from within

And with that, you’re not just “burning calories.” You’re also changing how energy, protons, and photons move through this collagen–water network that Becker was so obsessed with.

In winter, when you are not getting as much natural light on your skin and in your eyes, having a strong internal “fire” can matter a lot.

I am not saying cold replaces sunlight. It does not. Sunlight gives you time-of-day information, spectrum, and signals that cold cannot.

I am saying:

When used wisely, gentle cold is one of the tools that helps your mitochondria stay responsive, warm, and capable of generating internal energy and light, instead of letting everything go sluggish and stagnant all winter.

What gentle winter cold could look like in real life

Here is the version that makes sense in a normal life (even with kids, work, and a heater 😉).

But again, always keep safety in mind:

If you have heart disease, uncontrolled blood pressure, serious illness, are pregnant, or have any condition where sudden temperature change could be risky, talk with your doctor first.

You should never force yourself to stay in water that feels terrifying, painful, or makes you feel like you cannot breathe.

With that said, here are some examples of gentle experiments:

1. The “just a bit cooler” bath

Run a bath that is warm, but not hot.

Let it be close to skin temperature or a little below, instead of steaming hot.

Sit for 10 to 20 minutes, focusing on relaxing, not bracing.

Ideally, your chest and torso are in the water, not just your feet.

You might get a little chilled by the end. When you get out and dry off, notice the rebound warmth and circulation.

If you’re not ready for this, you could start with a face plunge in colder water. (Did my family turn a champagne bucket that we received as a housewarming gift into a face plunge bowl? Mayyybe….)

2. The cooler finish

Take your normal warm shower.

At the end, turn the temperature down a bit, to where it feels cool but not unbearable.

Stay there for 30 to 60 seconds, breathing slowly.

Over days or weeks, you can extend the time or make the water slightly cooler if it feels good.

3. Short outdoor “cold and light” moments

This is where cold and light play together.

Step outside in the morning with less clothing than you would normally layer on, just for a few minutes.

Let your face, neck, and maybe your forearms feel actual air.

Combine that with morning light in your eyes, without sunglasses.

Go back in before you are truly uncomfortable.

You are giving your body a quick “yes, it is winter, yes, it is daytime” signal.

None of these are extreme. You are not trying to win anything. You are trying to speak gently to your mitochondria in a language they recognize.

How this fits the bigger story

For me, winter used to be about fighting the season.

More heat. More coffee. More screen time. More indoor everything. Then wondering why my energy, mood, and metabolism felt…on the slowww side.

Now I think more in terms of:

How can I honor that my body came from people who survived cold and darkness?

How can I give my system at least a hint of the signals it expects?

How can I support both my external light exposure and my internal “fire”…if you will…

So, for me, that looks like:

morning and daytime light whenever I can get it

protecting darkness at night

a little bit of sane cold to keep my mitochondria in check 😊

None of this needs to be perfect or extreme. It just needs to be clear enough that your body can tell what season it is and what you are asking it to do.

If your cells could share how they feel, I’m pretty sure your mitochondria would be nodding along right now…like, yep…yessss….

Your mitochondria have not forgotten where they came from.

Most of the time, they are just waiting for you to give them a chance to act like it.

xx,

Dinah

P.s., if you found this interesting, feel free to share, and I’d also really love to hear how/if you’re using cold for health this winter. Feel free to start a convo below!

Sources:

Fumagalli, M., Moltke, I., Grarup, N., Racimo, F., Bjerregaard, P., Jørgensen, M. E., Korneliussen, T. S., Gerbault, P., Skotte, L., Linneberg, A., Christensen, C., Brandslund, I., Jørgensen, T., Huerta-Sánchez, E., Schmidt, E. B., Pedersen, O., Hansen, T., Albrechtsen, A., & Nielsen, R. (2015). Greenlandic Inuit show genetic signatures of diet and climate adaptation. Science, 349(6254), 1343–1347. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab2319

Hanssen, M. J. W., Hoeks, J., Brans, B., van der Lans, A. A. J. J., Schaart, G., van den Driessche, J. J., Jörgensen, J. A., Boekschoten, M. V., Hesselink, M. K. C., Havekes, B., Kersten, S., Mottaghy, F. M., van Marken Lichtenbelt, W. D., & Schrauwen, P. (2015). Short-term cold acclimation improves insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nature Medicine, 21(8), 863–865. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.3891

Matsui, H., & Matsuo, Y. (2020). Proton Conduction via Water Bridges Hydrated in the Collagen Film. Journal of Functional Biomaterials, 11(3), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb11030061

Peres Valgas da Silva, C., Hernández-Saavedra, D., White, J. D., & Stanford, K. I. (2019). Cold and Exercise: Therapeutic Tools to Activate Brown Adipose Tissue and Combat Obesity. Biology, 8(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology8010009

Tafur, J., Van Wijk, E. P. A., Van Wijk, R., & Mills, P. J. (2010). Biophoton detection and low-intensity light therapy: A potential clinical partnership. Photomedicine and Laser Surgery, 28(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1089/pho.2008.2373

Van Wijk, R., Van Wijk, E. P. A., Pang, J., Yang, M., Yan, Y., & Han, J. (2020). Integrating Ultra-Weak Photon Emission Analysis in Mitochondrial Research. Frontiers in Physiology, 11, 717. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.00717

Hello, so happy to connect with you 🤍 I just subscribed to your content, and I hope you feel like subscribing to mine too 💌 xx

Beautifully written—thank you for illuminating the adaptive wisdom within our mitochondria. I’d add that on a metaphysical level, colds are not merely seasonal disturbances; they often show up how up when you've been pushing too hard for too long.

When you've been overextending, ignoring what needs attention, your body forces the pause you won't give yourself.

The mucus, the fatigue, the congestion—your system saying: I need to catch up.

This goes beyond immunity. It's about permission. The cold arrives when you finally allow yourself to stop, and your body can process what the pace buried.